Chess in 3D with Python

Today I felt compelled to look at putting Chess into a 3D program using its Python library to create the geometry and leave it to the program to handle the rendering. If it helps, kind of think of it as Blender.

I wasn’t really interested in spending my time writing a library for dealing with maintaining the board state or rules of Chess which is where the python-chess (Docs, GitHub) comes in. This package takes cares of all of that plus has an additional feature that made this project easier. It supports being able to connect to a chess engine like Stockfish using the Universal Chess Interface (UCI). In practice what this meant was instead of having to spend time setting up input for being able to select pieces and move them about and deal with two players as well as playing the game. I was able to set-up it up to battle two computers against one another.

I started looking for 3D models to use for the pieces and I started with sites for 3D printing pieces. However they never looked quite right and after spending about an hour looking around, I came across a set on GrabCAD by Allan Morel. These models were incredibly detailed and they started me thinking that I didn’t really want something as detailed as it means the file size for the assets will be larger. I started trying to simplify down the facet count but it never really looked right. I realised the keyword I should have been using was low-poly and I came across some that looked nice but at this point I had already prepared the first set ready for use and didn’t want to delay coding any longer.

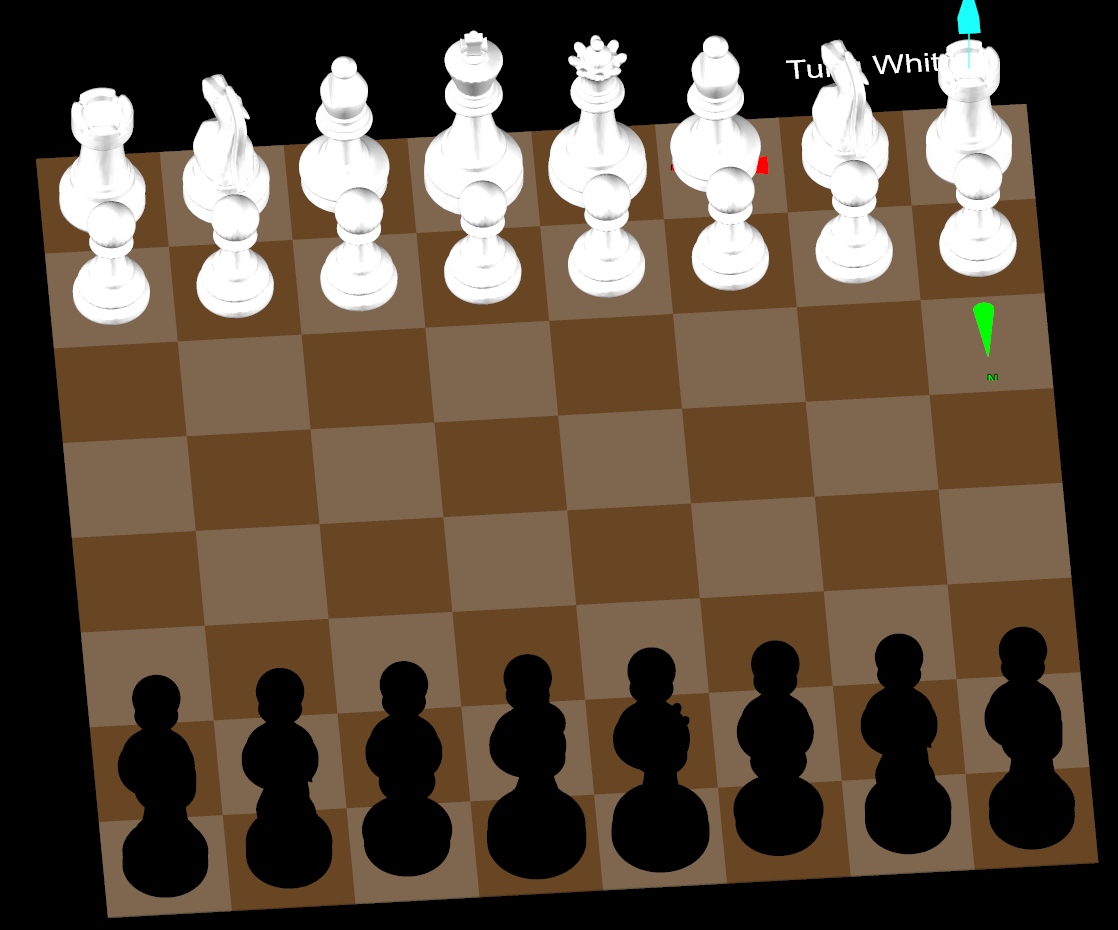

With that sorted out, I was now ready to draw the board. That was fairly easy as the library provides the position (known as the square index) of each piece so iterating over it and translating the square index into a row and column and then into the screen space did the trick.

So it turned out the pieces were only about 2 units high where the squares they are sitting on are about 32 units across. That was rather a simple change as I just needed to scale the pieces which could be done within the program’s graphics engine.

Now that I had the board done with the initial pieces I could see two problems. The first problem is the knights are not symmetrical and thus the white knights seem to be facing the wrong way. The bishops also aren’t symmetrical but they aren’t as noticeable and I am really not bothered about that. If anything it is somewhat nicer that they aren’t looking at a mirror image of themselves. The second problem is the black pieces look way too black mostly because the graphics engine doesn’t cast shadows onto them. They look like they are coated in the darkest known substances that absorb about 99.97% of light. As I mentioned, I won’t worry about the first problem but the second is a rather easy fix. I can simply change the colour from black (255, 255, 255) to charcoal (54, 69, 79).

Next up was to re-draw the board state between moves. I wasn’t interested in implementing animation to show the pieces get picked up and moved along. However this made me somewhat worried because the library didn’t represent pieces with unique identifiers on the board. This means when you are looking at a board before and after a move is played then you have no idea which pieces were moved. For example, you are told there is a white knight in this square and a white knight in that square rather than white knight 1 is here and white knight 2. This means technically what you might see in my implementation is one knight jumps to the position of the other knight and then that knight moves to the position of the first (or even its new position). This would likely be a non issue when dealing with the animation aspect because I would see the information that says the piece in this square (which is a knight) is being moved to this other square.

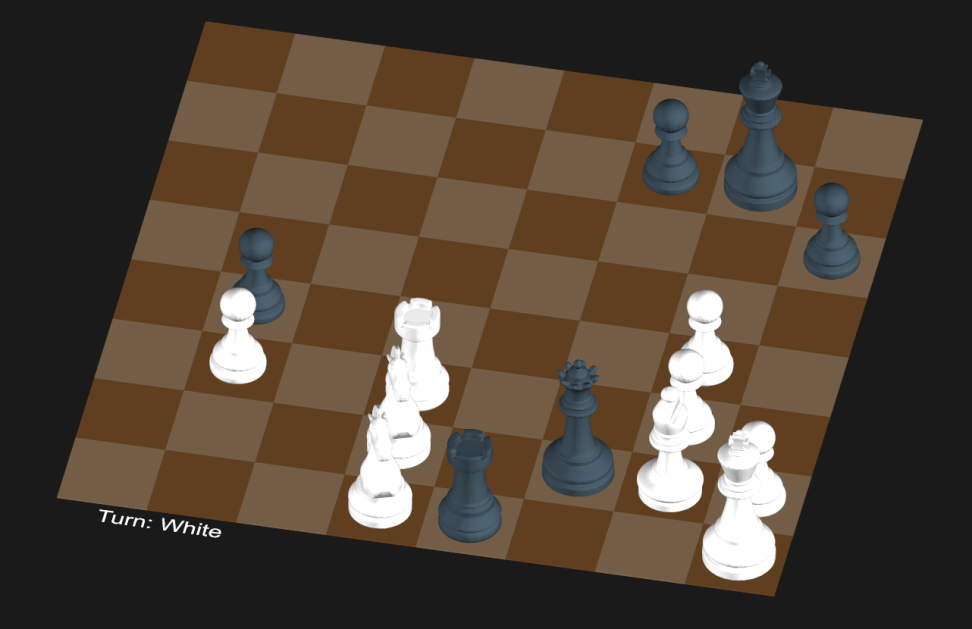

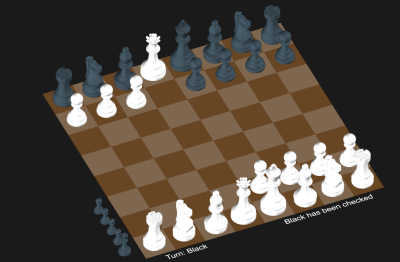

However after watching the AI play around a bit I spotted a problem:

So onto the next problem was I hadn’t implemented capturing. When one piece moves into the same square as an opponent piece then that piece captures it. At this point, all I had done is look at what pieces were on the board and where and moved them around. I haven’t accounted for it if the piece is no longer on the board.I didn’t end up looking to see if the library knows which pieces have been taken.

This fell out as a consequence of how I implemented the code to find what pieces to move. After moving all the pieces around on the board, I was left with a list of of pieces that weren’t found on the board. This list thus contained the list of pieces no longer on the board. Now I had two choices here, to delete the pieces once they are captured or move them into a capture area along the side of the board.

Deleting the pieces here means to remove them from the game and graphics engine. I wanted to do the latter option. I started doing that but there seemed to be a problem so I switched to the delete method for this next screenshot.

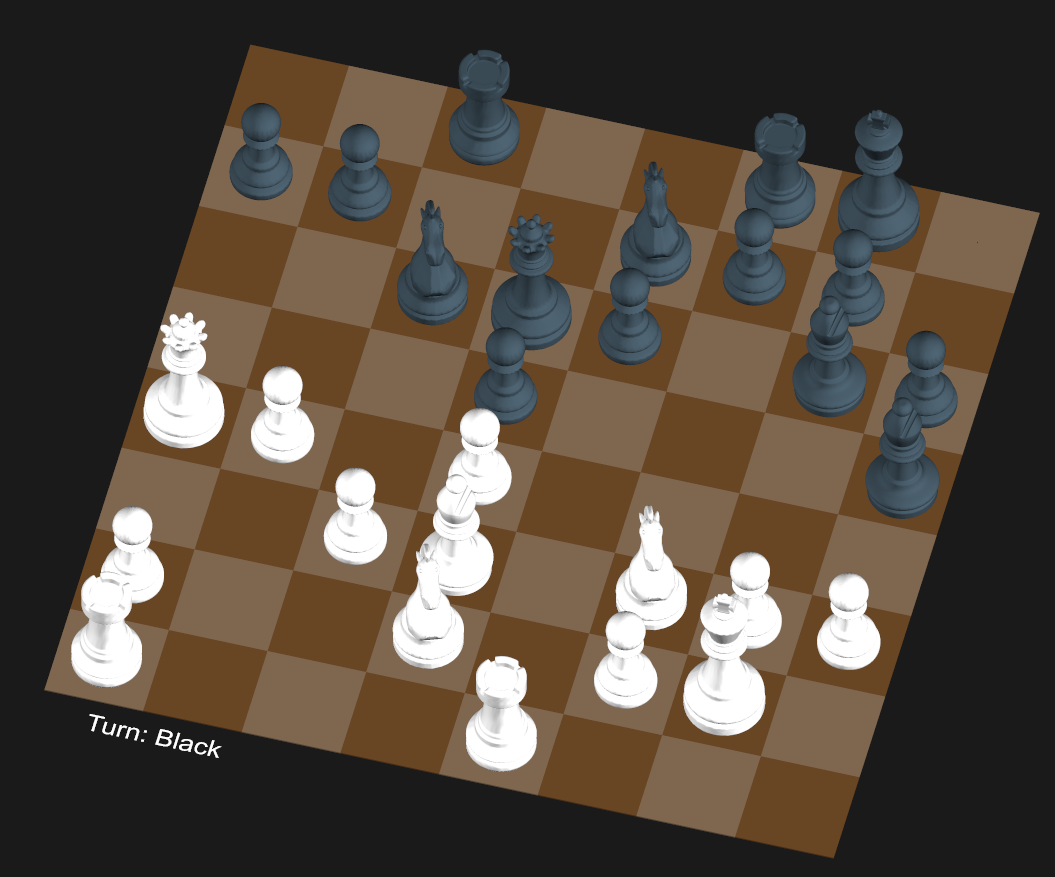

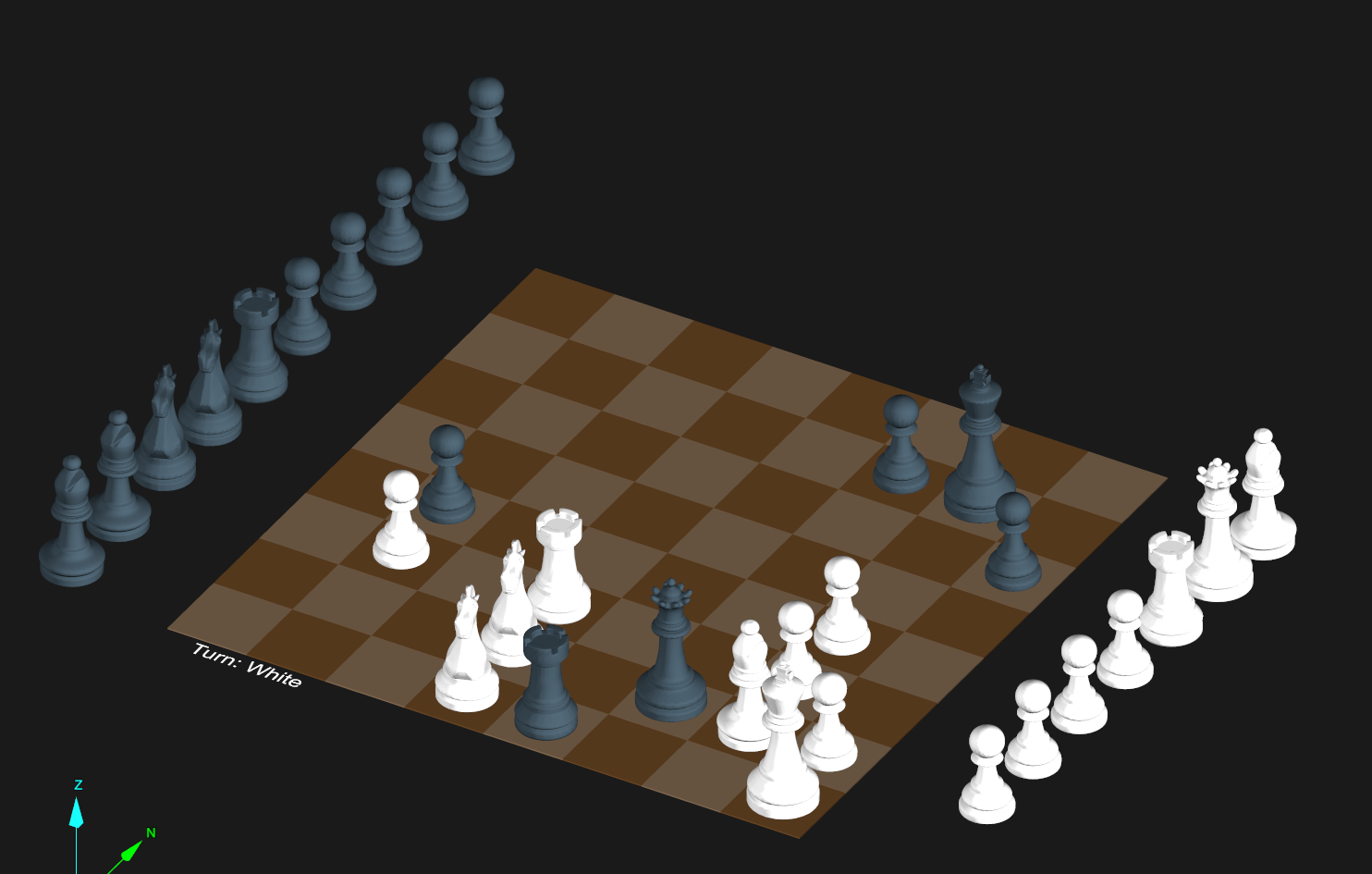

That is the board state of a game played by Kasparov vs Karpov in 1985. This was easily replicated by copying the Forsyth–Edwards Notation (FEN) for the board state and setting the board to the state. This is a feature of python-chess. FEN describes the board and what pieces are there. Consecutive empty space is represented as a number so it is naturally compressed. This is a rather nice feature as it meant I could get the board into a certain feature which comes in handy later.

After seeing that work, I got back to fixing the capture zone. I was able to get them to appear along the side like I wanted quite quickly.

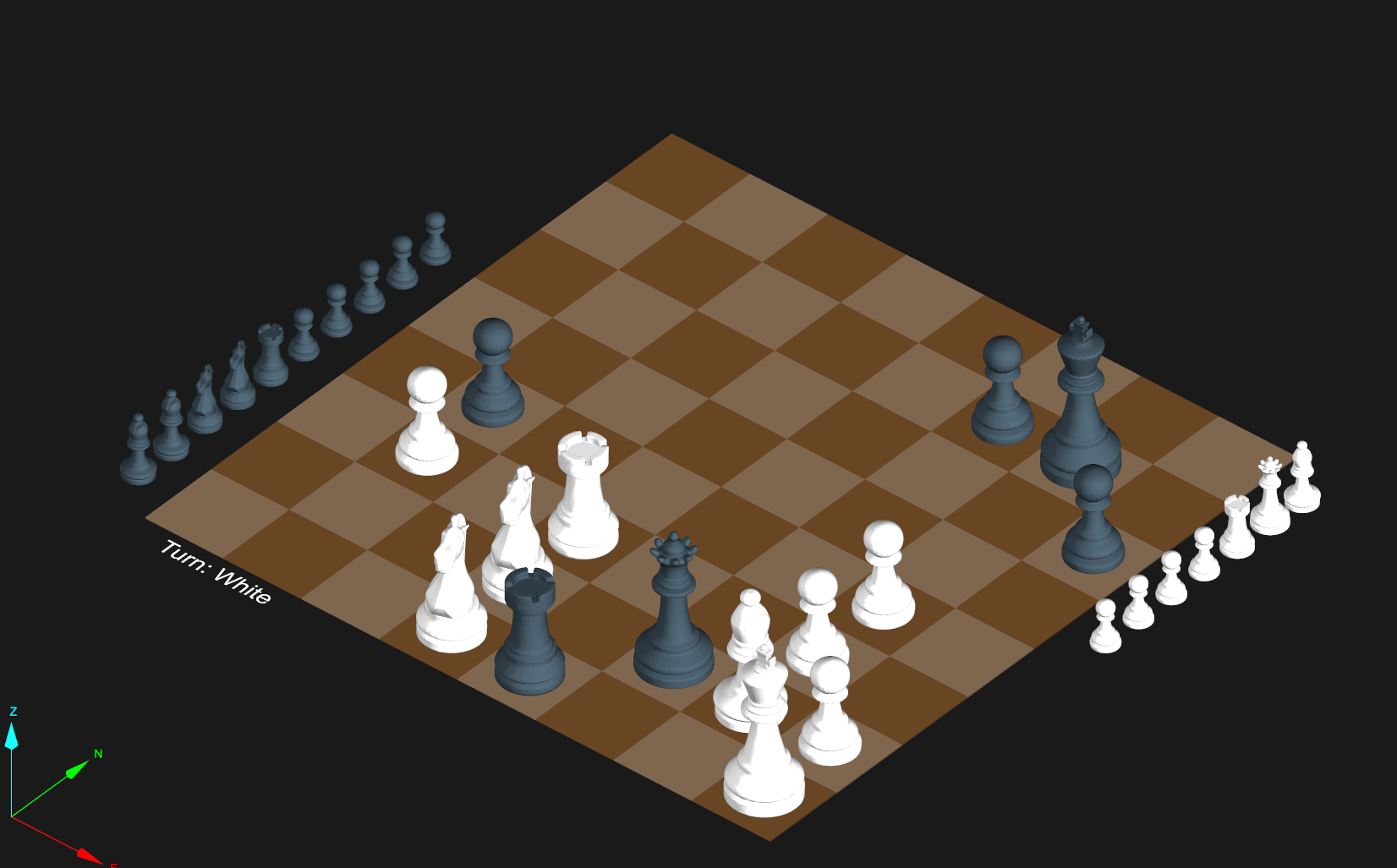

Yet as you see they take up a lot of space and look quite distracting. On the space side, there are potentially 15 captured pieces. But the board is only 8 pieces across if they are evenly spaced so it looks like they are also overflowing. The simple solution here was to scale down the captured pieces by 50%. The end result looks quite nice

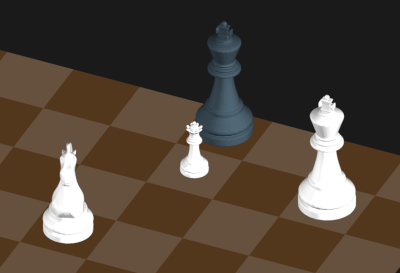

The next issue was noticed because of the side effect of shrinking the captured pieces. When a pawn makes it to the end and gets promoted it would often become a queen. But the problem here is it would be a small queen (or you might say princess).

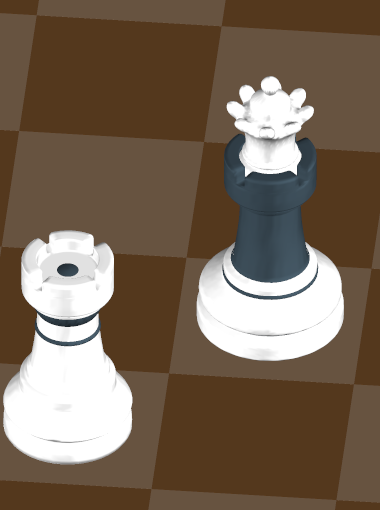

This one was an easy fix as it required resetting the size of the pieces back after promotion. The next problem I ran into was what would happened if there was already a queen when a pawn is promoted. Part of the problem was I assumed that a side would have 16 pieces and those 16 pieces would be the same type as they started as. So each side would have 8 pawns, 2 knights/rooks/bishops, a king and a queen. So if it looks for a ‘queen’ and can’t find one so I needed to then convert one of the pawns into the desired type.

Of course, when I was about to double check what happens when the two queen problem occurs, the AI didn’t do that. The next two games I watched the AI play never got into a situation where they would end up with two queens. In the end, I decided to cheat and use the FEN notation to put four pawns at the end of the board. If I had known I was going to use the screenshot again I would have tweaked the board. For example, castle the king and remove the defending forces from in front of the pawns.

With that complete the last thing was to add support to saying game over. After this one I also looked into adding information about who won or if it was a draw why.